Keith Sisman Ramsey church of Christ, England - Traces of the Kingdom

THE WORD BAPTISM AND THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

With certainty it can be guessed that the word Baptism was in use in Europe including Britain from the year 170 onwards. At this time the British people spoke one or more of the several Celtic dialects, Latin or a Romano-Celtic dialect. Greek was not spoken in the west, Latin being the official language. For this reason the Greek Scriptures were translated into Latin from around 157 (The Old Latin version). Jerome's Vulgate (official Catholic version) did not appear until the year 400, and did not fully replace the old Latin until as late as the 900s.

As the following pictures from across Europe show, baptism in times past was understood to be immersion.

Baptising in Britains church buildings did not begin until about the year 627 when king Edwin built a baptistery, to be baptised in.

Picture below is believed to be this baptistery, which is in the church of St. Martin's, Canterbury. In the time of the Norman kings (1100s) it was adapted for infant immersion.

Standing beside the baptistery is my daughter Anna.

In the year 689 king Inas, Ine or Iva of the West Saxons made the law that infants should be baptised (triune immersed) within thirty days of their birth. He also made it an offence to break Sabbath laws and gave the right of sanctuary in church buildings. Further laws or church councils (synods) in Britain confirming immersion as the, or a, mode of baptism were passed in 821, 1106, 1172, 1195, 1200, 1217, 1220, 1224, 1240, 1287, 1306, 1422, 1547, 1564 and 1571. In 1603 a cannon was passed in the Church of England declaring both immersion and aspersion acceptable modes, although aspersion had been practised previously. In 1645 sprinkling was declared favourable and from this date immersion in the Church of England would disappear.

__________________________________________________________

This picture is of the full immersion font of the Anglican church at South Creak, Norfolk. It is one of seven rare sacrament fonts of that period. It was very similar to the one at nearby Little Walsingham, but unfortunately the panels here are almost entirely defaced. However, it is still possible to make the sequence out, and to tell that the extra panel was the Crucifixion. The font dates to 1460, a late date demonstrating the mode for baptism in this period was full immersion, though the candidate, an infant was wrong, the mode (full immersion) is correct.

__________________________________________________________

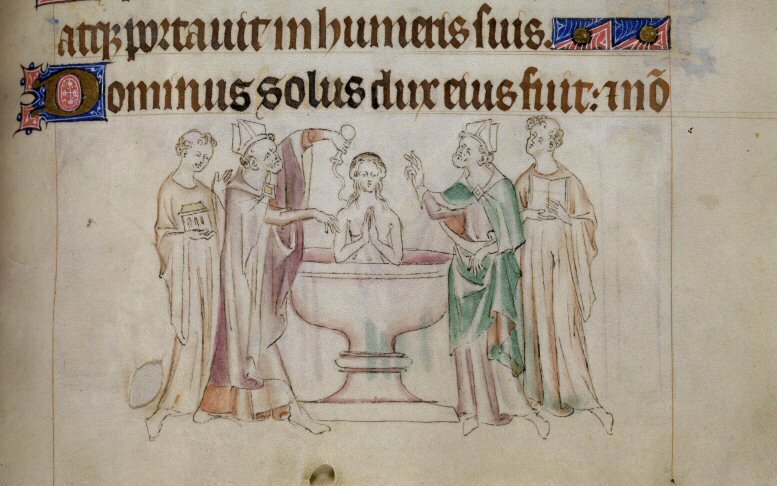

This picture is from England (London?); circa 1310-1320. It is from the work "Queen Mary Psalter", shows a bas-de-page scene of the Saracen emir's daughter, the mother of Thomas Becket, immersed in a large font, being baptized by two bishops.

Picture copyright © The British Library, used by permission. Shelfmark Royal 20 C. VII

__________________________________________________________

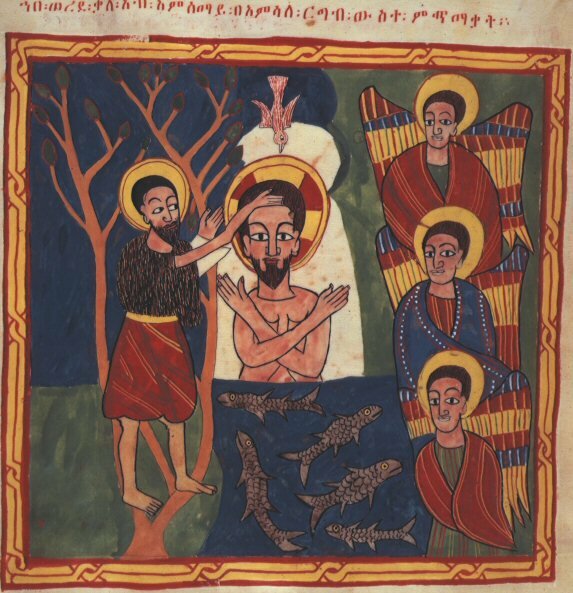

Picture of the baptism of Christ by John the Baptist. Parchment manuscript from the "Octateuch, Four Gospels and Synodicon. A work in the Ethiopic language. Produced at Gondar in the late 17th century. Even at this date, water is clearly in abundance for baptism, suggesting immersion.

Picture copyright © The British Library, used by permission. Shelfmark Or. 481

__________________________________________________________

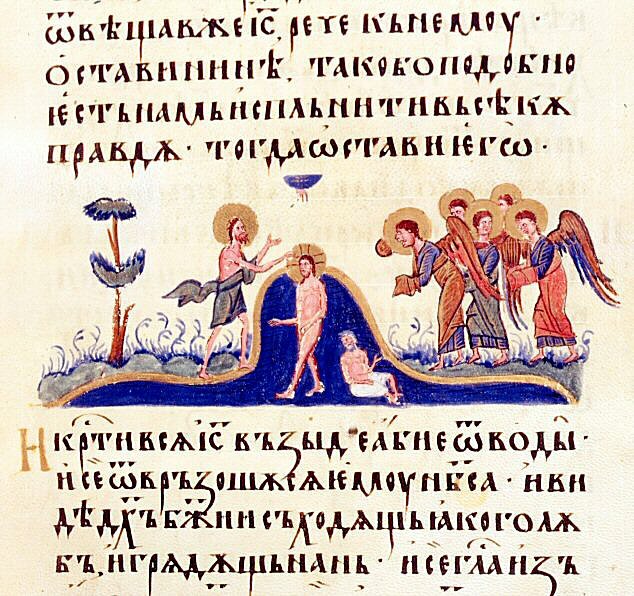

Baptism of Christ, the picture taken from The Gospels of Tsar Ivan produced by the scribe Alexander Simeon, at the Turnovo School, circa 1355-1356. language, Bulgarian Church Slavonic (Cyrillic uncial) .

Picture copyright © The British Library, used by permission. Shelfmark Add. 39627

__________________________________________________________

The Baptism of Christ. Paper manuscript copied at the monastery of St George an Armenian work called "The Four Gospels" by the scribe Awetik produced at Balu in 1437. We can see that much water is present to allow immersion.

Picture copyright © The British Library, used by permission. Shelfmark Or. 2668

__________________________________________________________

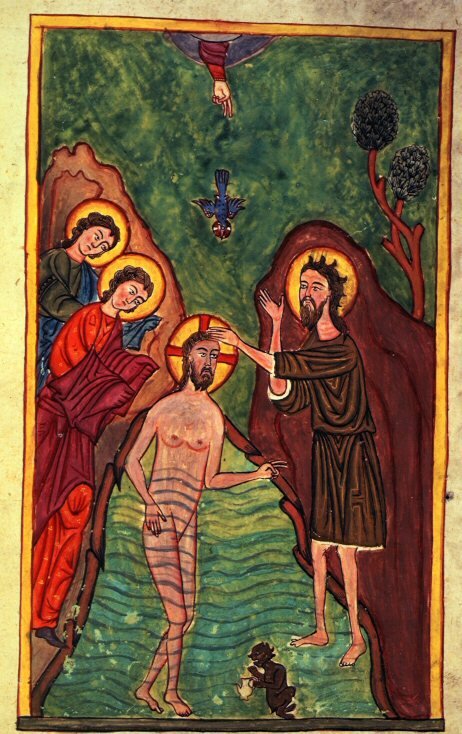

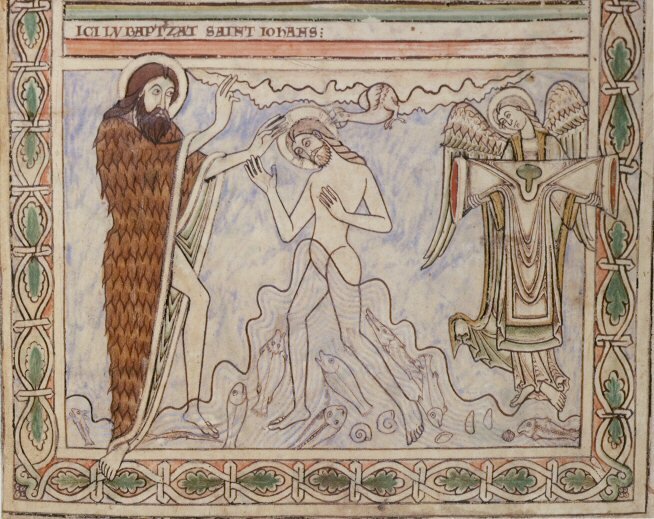

This picture was produced at Winchester, England [Priory of St Swithun or Hyde Abbey]; between 1121 and 1161. Title of the work, Winchester Psalter [Psalter of Henry of Blois; Psalter of St Swithun]. It is the "Baptism of Christ", where John the Baptist baptises Christ on whom descends the dove. An angel holds out the robe. It is of interest that much water is in the painting, the artist including several fishes.

Picture copyright © The British Library, used by permission. Shelfmark Cotton Nero C. IV

__________________________________________________________

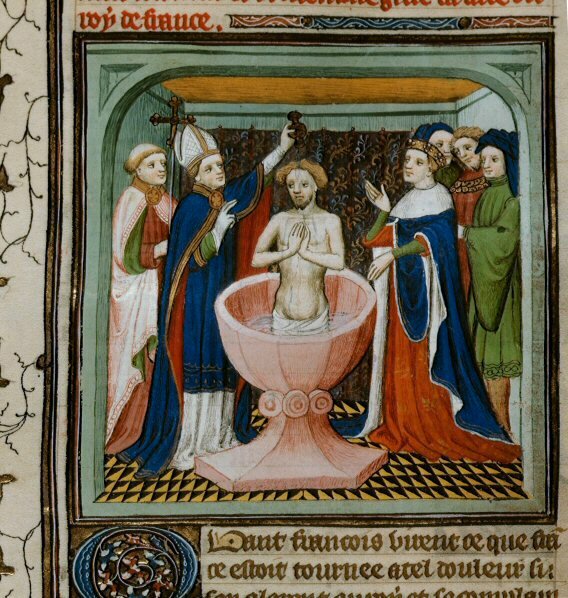

The baptism of Robert de Normandy by the Bishop of Rouen.

This picture is taken from the "Grandes Chroniques de France", a French work circa 1415.

An immersion font is used, as was typical in this period. The picture is of the baptism of Robert, son of William 11 Duke of Normandy who became king William 1 of England in 1066.

Picture, copyright © The British Library, used by permission. Shelfmark Cotton Nero E. II pt.1

__________________________________________________________

Baptism of Clovis

The baptism of Clovis, King of the Franks; the sainte ampoule, picture taken from the French Chroniques de France ou de Saint Denis, vol. 1, second quarter of 14th century.

History records that Clovis inherited his father's kingdom in 481, at which time he unified the Salian and Ripurian Franks. By 486 he had defeated the Roman general Syagrius, who ruled northern Gaul out of Soissons. In 493 he married the Burgundian princess Clotilda. In 496, after defeating the Alamanni, he was baptized, thus becoming the first 'Christian' ruler of post-Roman Gaul. By 506 the Alamanni were subdued, and the next year Clovis finished his expansion by taking Aquitaine from the weak Visigothic king Alaric II. On Clovis' death in 511, the kingdom was split between Chlodomer (Orleans), Childebert (Paris), Chlotar (Soissons), and Theuderic (Metz).

Picture, copyright © The British Library, used by permission. Shelfmark Royal 16 G. VI

__________________________________________________________

Baptism is the Latin and importantly, the English transliteration of the koin (common) Greek word, baptizo meaning to wash, immerse, sink or dip. It is as much an English word as it is Latin, and its meaning is to immerse.

When the word baptism was introduced to Britain it simply meant to immerse, as its Greek origin means. With various invasions through out Europe and Britain languages altered, but the word baptism remained in use as the Bible remained in Latin. In Britain language was infected by the Anglo-Saxons during the 400s, later French was to become the official language from 1066 with Latin the second. The English language itself did not come about until the 1200s and for official use from around 1400. Modern English started around 1500, interestingly the English language itself is not much older than the European colonisation of America!

Therefore we can safely conclude that in the British and later English languages that baptism meant to immerse, whilst the practice (mode) on the continent may have been to sprinkle or pour at an earlier date, this was not the case in Britain. Baptism by sprinkling or pouring did not come about in Britain until the 1620/1640s onwards.

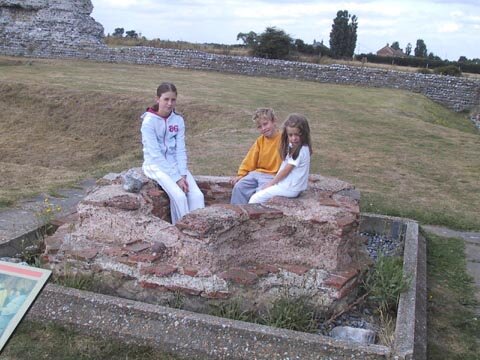

Below is the oldest baptismal basin in the UK. It is pre-Catholic and is found in the Roman castle at Rvtvpiae (Richborough, Kent). This baptismal bath has been dated to the third century and despite the efforts of historians to prove otherwise, is outside of any church building. It is likely to have been built after the year 167 when Christianity was legalised under king Lucius, the first country to legalise Christianity. From that time Christianity would fall to the influx of pagan practise.

Its important therefore to note that in Britain before the time of Wycliffe (1280s), and continuing to the time of Tynedale (died 1536) and the 1611 King James Bible versions that Baptism meant to immerse, for scholars, theologians and ordinary folk. From the 1640s onwards in Britain, sprinkling and pouring became the common mode for Baptism. Therefore in the time period to the 1640s it was the candidate rather than the mode that needs questioning. It is likely that Wycliffe understood the nature of believers baptism, Tyndale certainly did. The translators of the King James understood baptism by immersion but the candidates to be infants as according to church tradition. It therefore can be seen as to how translators have continued to use the word baptism, following the KJ and earlier English versions, whilst at the same time the mode has been changed from immersion to sprinkling or pouring, by the established denominations.

In many English (C of E) church buildings two baptismal fonts can be found, one for infant immersion and one for present day infant sprinkling/pouring. The church building at Crowland Abbey, Lincolnshire is typical of this, the older immersion font (twelfth century) is still incorporated in the building structure, whilst the more recent (fifteenth century) font originally for immersion but now for sprinkling stands in proud display, for every one to see. The original font was placed in the building entrance because baptism was required before entry into the church could be made. We can see therefore in early English history that the mode of Baptism is to immerse and that is why the word was retained, because the mode is in the word. The idea that modern Bible versions need to translate the word baptism to immersion is wrong, its not the word that needs altering, but the mode. It goes without question that the mode for baptism is in the very word itself, in the original and every day Greek, baptism means to immerse, sink or to dip, it cannot and does not mean to sprinkle or to pour. Changing the word baptism to immersion though does not help, to immerse babies is contrary to scripture even if the mode is correct. In scripture the mode is immersion for believers, for the remission of their sins upon confession and repentance, where upon they are added to the people of God (His church) who are in Christ.

Picture is the outside of the Abbey church at Crowland, Lincolnshire. It is still in use and is the Parish Church for the area, being over thirteen hundred years old. The first converts would have been baptised as believers, by triple immersion. Later infant baptism (by immersion) took over. After 1620 the mode was altered to sprinkling.

Tabitha my daughter, then two and a half, stands in the original twelfth century baptismal font.

It is located in the entrance to the church building as people entering the 'Church' had to be baptised first.

As can be clearly seen in the photograph baptising a baby by immersion presented no problem, the font being sufficiently large enough for this purpose.

__________________________________________________________

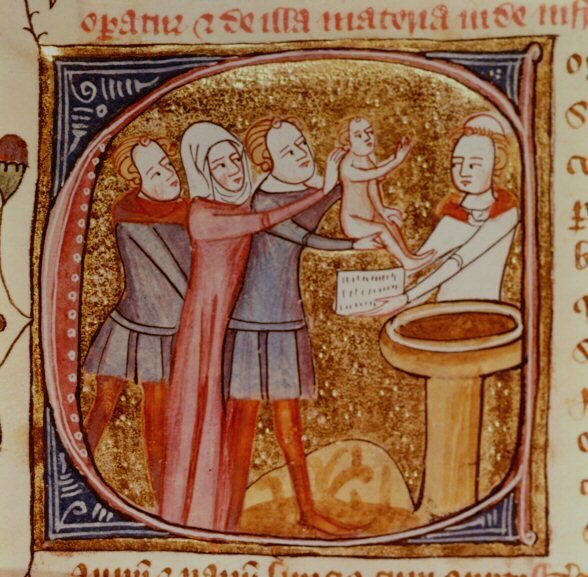

Picture, copyright © The British Library, used by permission. Shelfmark Royal 6 E. VI

As this picture from England (London); circa 1360-1375 is from the work "Omne Bonum" by James le Palmer, shows a scene showing the godparents presenting an infant to a priest during the Catholic sacrament of baptism. Importantly, the mode shown is immersion.

__________________________________________________________

Picture from France; circa 1390s is from the work "Chroniques de France ou de St. Denis", shows a scene of the baptism of Isabella, daughter of King Charles V of France. Again, importantly, the mode shown is immersion.

Picture, copyright © The British Library, used by permission. Shelfmark Royal 20 C. VII

__________________________________________________________

A Muslim full immersion bath can be viewed by clicking here

__________________________________________________________

To learn more on what the Bible says on Baptism, visit the web site below:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In this prior to 1600 in the English language people understood that the mode for baptism was by immersion, as the above pictures and photos confirm, at first correctly for adults (believers), then later for infants and eventually, infant sprinkling.

The idea that Rome from an early age had full control of all religious matters in Europe is not borne out by the facts. Whilst Latin speaking, much of Europe was Orthodox Christian by tradition. By using the Scriptures they were able to come to an understanding of New Testament Christianity which was often strongly resisted by Rome until the Popes were prepared to use violence to defend their power.

What follows is a brief but untold tale of the spread of pure Evangelistic Christianity across Catholic Europe and into England from the fourth century onwards - Traces of the Kingdom: